Disclaimer: ANOAQA do not condone taking a life. But we urge you to understand what drives a person to such a point.

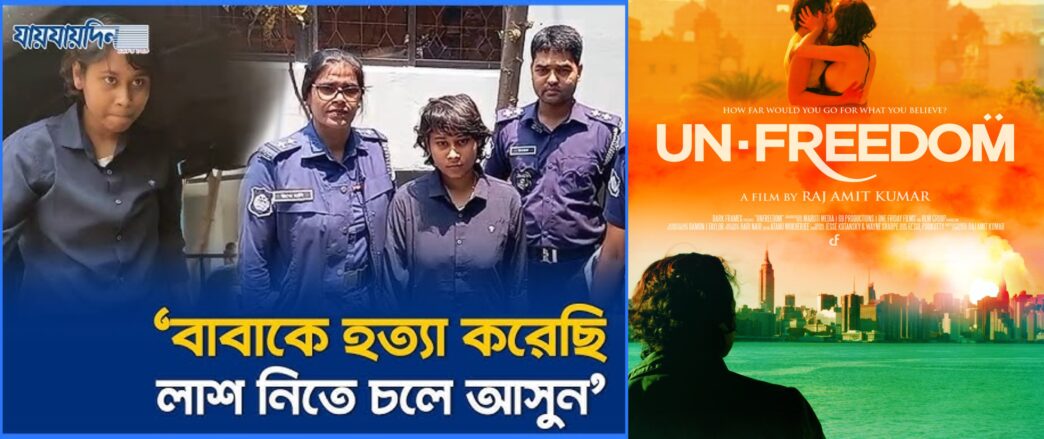

On May 9th in Bangladesh (Savar), 23-year-old Jannatul Jahan Shifa called 999 and calmly stated, “I have killed my father. Come take his body.” She made no attempt to escape, offered no resistance, and quietly waited to surrender herself to the police.

Most scrolls rushed to ask: Was this insanity, drunkenness or something darker?

But that question itself is a form of denial. The question is: why was Shifa left with no other way out?

According to reports, Shifa had endured four years of repeated rape by her own father after her mother’s death. She reported him. She pleaded with neighbors. She filed a case at Shingra Thana in Natore. But her father was granted bail. The case went cold. Shockingly, a woman who filed a rape case against her father—was forced to continue living under the same roof as her alleged rapist, without any state intervention to ensure Shifa’s safety or protection.

And then the victim became the accused.

As is so often the case in Bangladesh, the system didn’t just ignore survivor—it punished her. She was branded a “BAD GIRL,” whispered about, shamed, and dismissed. They said. Possibly a lesbian. Possibly a trans man. So her truth didn’t matter !

The system abandoned her. The law betrayed her. And society smothered her pain beneath layers of denial, suspicion, and prejudice—simply because she looked gender-diverse. On their lips, a slur: “Spoiled girl.”

This isn’t an isolated story. It’s one thread in a much larger pattern.

Across South Asia, non hetero women, gender non-conforming individuals—and often young girls deemed too “Masculine”—are subjected to what is chillingly called “Corrective Rape.” The goal is to punish and “Fix” them. To erase identity through brutality.

This form of violence is almost never acknowledged by the state and rarely prosecuted. Shifa’s story echoes the banned Indian film Unfreedom, where a father arranges his daughter’s rape to “CURE” her queerness. Except Shifa’s story wasn’t film. And this time, the daughter fought back.

What options did she have?

There are no state-run shelters in Bangladesh for survivor of spousal rape or domestic abuse or gender non-conforming women. Landlords rarely allow rent to single women. Survivors of domestic violence are forced to live under the same roofs as their abusers—with no intervention from the state.

And yet, after enduring years of trauma, society once again turned against her—mocking her gender and sexuality with fresh waves of bullying and gossip.

People scrutinized her haircut, her gait, her clothing. “She doesn’t look like a woman,” they sneered. As if her appearance somehow erased her pain.

Her Facebook post, made moments before she surrendered, wasn’t a cry for attention. It was the final note of someone who had screamed for help for years—and been silenced. A desperate claim to agency. A final act of self-defined justice in a society that offered her none.

And now, as videos circulate online dissecting her “masculine” demeanor, we ask again: Why did a bad girl kill her father?

But that’s a ridiculous question.

We must focus on asking the right, constructive questions –

- HOW MANY MORE SHIFAS MUST DIE—OR KILL—BEFORE THE STATE ACKNOWLEDGES ITS COMPLICITY IN THIS CYCLE OF VIOLENCE?

- HOW MANY DIVERSE WOMEN MUST ENDURE “CORRECTIVE” RAPE WHILE THEIR PAIN IS ERASED BY PREJUDICE AND SHAME?

- WHEN WILL THE STATE FINALLY ACKNOWLEDGE THAT QUEER LIVES ARE WORTHY OF PROTECTION—AND NOT PUNISHMENT?

Shifa didn’t only call out her abuser—she laid bare a system built to silence survivors. A society that mocks a potential rape victim for her haircut, and dismisses her cries for help because she doesn’t conform to traditional ideas of femininity.

We failed her—long before the knife was drawn.

Let us not make a spectacle of her story. Let us make it a mirror.

Because Corrective Rape was not one tragedy. It was one too many.